In the 15 January 1915 edition of The Lichfield Mercury, the first of three instalments of the diary written by Captain Morris Boscawen Savage, the Officer Commanding “A” Company, 2nd Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment, was published. Subsequent extracts were printed in the 22 January and 29 January editions of the newspaper, under the title “The Doings of the 2nd South Staffs. Regiment – Leaves from an Officer’s Diary.”

Born on 14 March 1879, Savage was commissioned as a Second-Lieutenant in the 3rd Militia Battalion, The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment) on 12 January 1898 and transferred as a Second-Lieutenant to The South Staffordshire Regiment on 20 May 1899. He was promoted to Lieutenant in 1900 and advanced to the rank of Captain in 1908. Between 1909 and 1912 he served as Adjutant of the 2nd Battalion in India and at Lichfield. In 1912 Savage was seconded to serve with the Egyptian Army and posted to the Sudan. He arrived back in England early in 1914 and at the outbreak of the war was serving with “A” Company of the 2nd Battalion.

Captain Savage’s account covers the period from 11 August, when the 2nd South Staffords left Aldershot for France, until he was wounded on 23 October at Pilckem.

11 August:

The Battalion, made up to war strength, marched off the Barrack Square, Badajos Barracks, at about 12 midnight, and entrained at Farnborough Station. Before the order to mobilise was received the Battalion was very weak, and to make it up to strength it required about 600 Reservists; a number of young officers of the Special Reserve also joined the Battalion. The Reservists were well behaved, and there was not a case of drunkenness among them. The King inspected the Battalion a day previous to their departure, and complimented them on their appearance.

On the march to the station all ranks were very quiet; probably all were wondering what the future had in store for them. How few of the men out of those fine battalions which left Aldershot will ever see their native land again, unless in a wounded or sick condition.

12 August:

The Battalion left Farnborough for a destination unknown, which eventually proved to be Southampton. The last occasion on which the Battalion visited Southampton was when it arrived on the H.T. Soudan in 1911. There were a great many non-commissioned officers and men in the ranks who were present on that occasion.

The Battalion, together with the King’s Regiment, embarked on the H.T. Irrawaddy. The ship in question was a small one, and the men were very crowded, but fortunately the weather was fine. The Irrawaddy put into Sandown Bay for a short time, together with several other transports, probably to await orders to proceed as soon as the Navy reported the Channel free of any German warships.

13 August:

The H.T. Irrawaddy arrived at Le Havre early in the morning, and the Battalion soon after disembarked, and fell in on an open space just clear of the dock sheds, and proceeded to march to the rest camp, which was some six miles away on the hills overlooking Havre. The troops were very well received by the population, and the streets were decorated with flags. The day was very hot, and a number of men fell out on the road up, from heat and exhaustion, probably caused by the sea journey. The inhabitants were very kind, and rendered every assistance to those who were unwell. Even small children marched alongside, in some cases carrying rifles and packs for the tired soldiers.

On the whole, however, I do not think we were very proud of ourselves when we arrived in camp, but in less than a months’ time the same men had every reason to be proud of their marching powers, and once more showed that there were few, if any, troops in the world who could march better (Retreat from Mons.)

14 August:

The Battalion remained in the Rest Camp all day. The Rest Camp was a very large one, and there were tents for both officers and men. The men carried out parades and received instruction in musketry and other most necessary parts of a soldier’s training. A Frenchman, who could speak English very well, carried out the messing for the officers. I often wonder now if he was a spy, knowing as I do how wonderful the German spy system is.

15 August:

The Battalion left the Rest Camp very early on the morning of the 15th to entrain at the station for a destination unknown. Soon after we left camp a violent thunderstorm came on, and torrents of rain, and most of us got very wet on the way.

We entrained at one of the dock stations; about 40 men were put in each truck. This type of conveyance was new to us, also the trucks for transport, but in a very short time all were on board the train and anxious to leave. The station was a very large one, and there were quantities of stores there for the British Force.

Our reception along the line was most cordial; at one place the French provided coffee with brandy in it, which was much appreciated by all.

At every station where the train stopped the public clamoured for souvenirs and in return gave flowers; a badge, button, or any such article, was all they required. The badges of the British Army will be found in houses all over France and Belgium for a number of years.”

16 August to 20 August:

We arrived at Wassigny early on the morning of the 16th, and from there marched a few miles to Iron, where the Battalion went into billets.

On arrival at the place the public turned out, and the Commanding Officer and Adjutant were presented with an address and a bouquet apiece. The Commanding Officer replied to the address of welcome, but as I was not there at the time, I am unable to state what he said, but I am sure it was to the point.

“A” Company was billeted in the farm buildings of a Mr. Picart and another smaller farmer. Monsieur and Madame Picart were both charming, and did everything to make our stay with them a pleasant one. We lived off the fat of the land and so did the men. More than one man remarked to me. “If this is active service, I wish I was always on it.” Poor fellows, it was not long before they found we were on active service of a very trying nature. Our time in Iron was not wasted; each day marches and parades, as well as inspections, took place, and we did all we could to prepare ourselves for the struggle in front of us.

Owing to the war a large number of men had been called up to join the Army, and there were few to gather the harvest. The Commanding Officer kindly allowed men to assist the farmers in gathering the harvests. This pleased the inhabitants very much.

The drums and fifes of the Battalion used to play at Retreat, and this was very much appreciated by the inhabitants, who used to all turn out to listen to the music.

Monsieur Picart, our host, belonged to the Army Reserve, and each day used to take his turn in guarding one of the bridges near the village.

Iron was a pretty little village with a small river running through it. A portion of it was told off for bathing, and as the weather was hot, bathing parades took place and were much enjoyed by the men.

We all left Iron with regret, and the inhabitants I am sure were very sorry when we left, as the men had been well behaved, and had made themselves very popular.”

Second-Lieutenant Arnold Gyde, who commanded No. 7 Platoon of “B” Company, also recorded his memories of being billeted in Iron:

“Peace reigned for the next five days, the last taste of careless days that so many of those fellows were to have.

A route march generally occupied the mornings, and a musketry parade the evenings. Meanwhile, the men were rapidly accustoming themselves to the new conditions. The officers occupied themselves with polishing up their French, and getting a hold upon the reservists who had joined the battalion on mobilisation.

The French did everything in their power to make the Battalion at home. Cider was given to the men in buckets. The officers were treated like the best friends of the families with whom they were billeted. The fatted calf was not spared, and this in a land where there were not too many fatted calves.

The Company “struck a particularly soft spot.” The miller had gone to the war leaving behind him his wife, his mother and two children. Nothing they could do for the five officers of the Company was too much trouble. Madame Mere resigned her bedroom to the major and his second in command, while Madame herself slew the fattest of her chickens and rabbits for the meal of her hungry officers.”[1]

Captain Savage’s diary continues:

21 August:

We left Iron at 6 a.m., and marched to Landrecies, when the Battalion went into some empty French Barracks for the night. The barracks had been left very untidy and dirty by the outgoing regiment.

The officers of the Company were billeted in a villa close to the barracks. We lived in the drawing room, and slept on mattresses on the floor. The owner of the house was very kind and obliging.

Landrecies was soon after the scene of a sauguinary battle between the Guards and Germans. The Germans were repulsed with the loss of about 1,000 killed.

22 August:

Marched at 5 a.m. to Hargny (sic – Hargnies), and the men of the Company were obliged to bivouac in an orchard, owing to there not being sufficient room in the houses for them. One platoon of the Company was sent out on outpost to protect the Artillery.

23 August:

The Battalion marched at 2 a.m., we halted on the road, and soon after crossed the frontier and entered Belgium for the first time. Information was received concerning the position of the Germans. On the march we saw several regiments of the 1st Division in position.

The Battalion eventually took up a defensive position at Harmignies, with the Royal Berkshire Regiment on our right in the village of Vellereille-le-Sec.

“A” Company occupied a position on a spur between Harmignies and the Royal Berks. Regiment, which the Company took over from the scouts of the Royal Irish Regiment.

We started to entrench ourselves. In the afternoon our artillery opened fire, and soon after the enemy’s replied. Some horses belonging to our Cavalry were fired on by the Germans, and a shell exploded in the middle of them and killed a number of the horses. A fierce artillery battle now took place between our artillery and the German artillery, but our guns did not appear to suffer at all, although the Germans had many more guns. The German artillery opened fire on the village occupied by the Royal Berks, with field howitzers, and soon set the place in flames, and it seemed impossible for a man to live in such an inferno, but I heard from the Berkshires later that they only had one man wounded.

In the afternoon the German infantry advanced to attack, but met with such a warm reception from our 18 Pdrs. that they remained where they were and made no further advance.

The artillery duel went on between our artillery and the enemy until it was dark. It was a fine sight. The shells went over our heads, and for some reason or other the Germans did not fire at us, and we made the most of our time improving our trenches in anticipation of attack.

When the darkness fell, the sky was red with the flames of burning villages.

I made my dispositions for the night, and sent out patrols well in front to give me early warning in case of attacks by the enemy, and we lay down and tried to take what rest we could, but I slept little.

During the night very heavy rifle and machine gun fire took place. The German searchlights were over us all night, and we kept well down in our trenches to avoid discovery.

William Cox, who as 7502 Sergeant Cox also served with the 2nd Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment, compiled his recollections in 1960 from notes he had written in 1914. He remembered the first day of fighting thus:

“23 Aug. 1914:- Crossed the Belgian frontier and passed the famous battlefield of Malplaquet. About two miles north of this came into contact with the Germans and experienced shell fire for the first time, just outside the village of Givries, entrenched and stayed the night. We had a few casualties. I learnt later that we were only a mile from the heavy fighting at Mons.”[2]

Captain Savage:

24 August:

The artillery duel was opened as soon as it was light. We received orders to retire as soon as the Royal Berks had withdrawn. I told off an officer and some men especially to let me know when they saw them retiring. I waited some time, but I could not see a sign of the Berks, but saw some of our Cavalry near this village, and decided to set spurs to my horse and ride to find out. I found the Cavalry in rather an excited state, as shells were falling about them, and in many cases two men were riding one horse, the other horses having been killed. The Cavalry told me that the Berkshires had been gone some hours, and that the enemy were advancing in force. I at once galloped back to the Company and started issuing instructions for a retirement, and soon after received written instructions for a retirement and soon after received written orders to retire slowly. As my lead platoon started started to retire I saw two battalions of German Infantry and some artillery come out of a wood about 1,200 yards to my front with the intention of advancing to attack. The German artillery opened fire and we started to retire. As the leading platoon retired, a squadron of our own Cavalry took up position on a spur parallel and to the right of the one we were on, and commenced firing rapid fire unto us as we retired. We waved to try and stop them, but it was no use. They had evidently taken us for the advance lines of the Germans. Fortunately the range was long and hit none of us, but several of us had narrow escapes.

We succeeded in withdrawing from our positions without loss, and were covered by the Cavalry. I ordered the Company to collect on the road under cover, and when I thought they were all withdrawn I followed there, and found one platoon still missing. I went back and brought it along, and sent the Company on. Owing to the Cavalry opening fire on us the machine gin limbers had not been able to retire, and as I had a horse I went back again to see if I could find them, and could not see anything of them, and the result was that the Machine Gun detachment had to carry the guns six miles. (The limbers eventually turned up, having taken another road.) We reformed the Battalion some three miles back, and then the Battalion continued its retirement, and we were shelled most of the way by the enemy’s artillery, but most of the shells burst very high, and did very little damage.

We were all very tired, having had little, if any, sleep the night before, and very little food. We arrived that evening at Bavai, where we hoped we should get some rest, but we had only time to have a snatch of food, when we were ordered out to take up a defensive position and entrench as soon as we got there. The Battalion took up a defensive line with its left resting on the road, the King’s Regiment carrying on the line to the far side of the road. It was hard to sight one’s trenches, as it was dark, but we soon got to work. There was a small farm behind the line occupied by the Company. With a pump we were able to get what water we required and fill our water bottles. We went on digging well into the night, and then lay down to take what rest we could.

25 August:

At dawn we continued work on our trenches, and also did what we could by clearing the foreground.

We received our first mail from England since we had left home, in the trenches.

At about 7 a.m. the King’s Regiment became engaged with the enemy, and firing was heard well off on our left. Soon after information was received that the German Infantry were advancing to the attack. An order was received by the King’s to retire, and the Company received an order to cover the retirement and then follow on a rejoin the Battalion. A platoon of “A” Company was sent to occupy the hedge round a white house near the road, and from there they opened fire on the enemy’s infantry, which could be seen in a wood 810 yards away. The German infantry had been firing at us for some time, but all their shots went high, and the only damage done was one man slightly wounded. After the King’s had withdrawn “A” Company followed them. The men were most disappointed when ordered to retire, as they were anxious to come to close quarters with the Germans.

We rejoined the Battalion and continued our retreat via Pont son Sambre to Maroille, covered by the Royal Berks. Regiment and Cavalry.

The march to Maroille was very hot, and we all arrived very tired. The Company was billeted in small houses along the main road near the bridge over the river. The Company had hardly got into their billets before a report was started that the Germans were advancing. Refugees, transports, carts, etc., came rushing back into the town shouting “The Germans are coming.” We at once fell in in our “alarm posts” and proceeded to the bridge which crossed the river in the direction from which the Germans were supposed to be coming. It was a revelation to see how keen tired soldiers were to have a go at the Germans. Cooks, pioneers, and every man who could get a rifle turned out with fixed bayonets, and the question on everybody’s lips was “Where are the Germans?” but the Germans did not come, and we returned to our billets.

The officers of the Company had a very comfortable billet in a house, the owner of which had married an Englishwoman, and as the whole family spoke English, one felt as if we were in England again. We were just sitting down to a hot dinner, the first square meal we had hope to have for five days, when we were suddenly ordered to fall in. It was dreadful leaving the good dinner, but the Germans were reported to be attacking one of the bridges, and there was no time to be lost.

The Company was detailed to hold one of the bridges over the river, and all the transports passed out that way.

The Royal Berks. Regiment were attacked at one of the bridges, but succeeded in holding the bridge, but they lost a number of men, and their wounded were being brought into the town during a greater part of the night.

26 August:

We marched out of Maroille at dawn, and no sooner had we left than the German shells started to fall into the town.

We met the French Army on the road, and started to take up a defensive position, but later on were ordered to make a forced march to Venerolles. On the way we passed the 4th Guards Brigade, which had taken up a defensive position to check the advance of the enemy.

27 August:

We went out on outposts for the night. It rained hard, and we all felt very far from cheerful.

Marched at 7 a.m. The Battalion acted as a flank guard, and marched via Guise.

When the Company withdrew, it marched in rear of Guards Brigade. In the way a German aeroplane flew over, and it was fired at by the troops.

The Battalion bivouacked at Mt. D’Oribuy, and threw out outposts.

28 August:

After dark we moved our positions, as the Germans were reported to be at St Quentin. Marched at 4 a.m., and halted at La Fere.

General French came into our camp and spoke to the men. He said “that he had just received a telegram from the French President thanking the British Army for their work, and that by their movement they had saved the French Army from destruction, and that he had never been more proud of being a British soldier than he was to-day.”

After a halt of two hours we resumed our march, and arrived at Amigny before dark, and went into good billets, and had an excellent dinner.

At 10 p.m. “A” Company was ordered out to hold a bridge at Condon. We found a large chateau at Condon, where we slept. We at once started to throw up entrenchments for the defence of the bridge.

29 August:

Made further dispositions for the defence of the bridge, and sent out patrols, and established observation posts.

The men brought in two men and one woman, whom they suspected to be spies. We sent them in to headquarters. The woman refused to be blindfolded. I think she was under the impression that we intended to shoot her. All tried to explain in French that we did not intend to do her any harm but it was no use, and she was eventually sent in without being blindfolded.

During the day the Royal Engineers prepared the bridge for demolition, and it was blown up during the night.

30 August:

We received orders to withdraw from the bridge at 6 a.m., and rejoined the Battalion at Armigny (sic). We marched through thick woods all day. The day was very hot, and water very scarce, and the men suffered a great deal from thirst. We bivouacked in a field near Coucy-le-Chateau.

31 August:

Marched 4 a.m.; went through Soissons and passed a lot of French refugees from Iron, some of our old friends being among them. We crossed the bridge over Aisne, and halted on the far side. A large number of French troops came over after us. We were short of water on the march, and the men suffered a lot from heat and want of water.

I had a wash in the river, alongside which we halted for two hours. A man from the King’s Regiment was accidentally drowned in the river. We continued our march at 2 p.m., and arrived at dusk at St Baudry. We altered our position after dark, and put out outposts on a steep hill, to the top of which we had moved after dark. Firing was going on not far from us all night.

Two incidents during the Retreat from Mons were later recalled by former Sergeant William Cox, in his reminiscence written in 1960:

“Started trekking again towards afternoon. Everybody ravenously hungry. The platoon spread out down the road for 200 yards. Passing a cottage I had a quick look-see inside. The occupants must have fled leaving the remains of a meal on the table and a canary in its cage. Thought I would look in the oven and to my surprise there was a lovely big cake still quite hot. It was promptly transferred to my haversack (looter!)

The same afternoon my platoon officer (about 19) asked me to carry his sword as he could no longer march with it. I told him I had enough to carry and suggested burying it as we would certainly be coming back. I dug a small place in the bottom of a hedgerow with my entrenching tool and marked the place on the map.”

Captain Savage:

1 September:

Marched at 3 a.m. We passed through the 4th Guards Brigade, who had taken up a position to delay the German advance. Our march was through wooded country in the direction of Villers Cotterets. We halted south of a wood for about an hour, and we could hear the action taking place between the Guards and the enemy. We received orders to march back and cover the retirement of the Guards.

The 6th Infantry Brigade was sent to try and assist a battery to withdraw their guns, which they were unable to do owing to the enemy’s heavy fire.

“A” Company received orders to move out and get up as close to the guns as possible. We were subject to a very heavy shell fire during our advance. The rest of the Battalion moved up through the wood to support the guns. A portion of “A” Company got as far forward as the railway line.

Owing to the advance of the infantry, the enemy were obliged to concentrate their fire on us instead of the guns, and the teams were brought up and the guns withdrawn. The Officer Commanding the Battery, as he galloped off, shouted to us and said we had saved his guns.

During the attack, Sergeants Bundy and Mullet, of the Company, were wounded, as well as several N.C.O.’s and men. I was hit in the thigh with a spent shrapnel bullet, but it did not draw blood – only made a large bruise.

After the withdrawal of the guns, we reformed and continued our march to Thurey, where we arrived after dark, and bivouacked in an orchard close by.

2 September:

Marched at 3 a.m., and arrived at Triibardeau at 7 p.m. The Battalion bivouacked under the trees in the grounds of a beautiful chateau, and we hoped to have a good night’s rest, but we received orders to be ready to move at 2 a.m.

3 September:

Marched at 2 a.m. via Meaux; halted twice during the day. The Second Division concentrated. We halted for the night at Bilbardeau les Vannes. Bad water supply. Bivouacked in the straw brought from ricks.

4 September:

Remained in bivouac until afternoon. Went out to take up position, but orders countermanded, and we retired, enemy’s shells following us.

5 September:

Left Voisins at 2 a.m. Marched via Foret de Crecy, and arrived at Chaumes. Company went forward and found outposts on high ground.

Saw lots of French refugees leaving place. We saw lots of French families with a couple of little trunks in their hands, leaving their comfortable homes and all they had behind, knowing full well that the Germans would loot all that was left behind, and in all probability their homes would be burnt.

We saw two poor old women of about 75 to 80 in one place assisting one another along a road from their homes, stopping about every 200 yards to rest. I don’t suppose they had been out for years, and there were no vehicles to take them; they had all been taken by the troops, or were packed full of refugees.

The sight of the French refugees leaving their homes enraged the men, and they heaped curses on the heads of the Germans.[3]

6 September:

Left Chaumes at 5 a.m. and advanced; halted about mid-day in an orchard. We saw some English aeroplanes for the first time, which came down close to us with information.

We marched again in the afternoon, and bivouacked at Chateau de la Fontaine. Company found one platoon for outpost duty. The Battalion was in reserve. A fine chateau near our bivouac, from which we got straw and water.

7 September:

Moved into the grounds of the chateau under the trees after breakfast. Battalion was issued with sheep to be killed for the meat ration, as our rations had been taken by another unit. Marched at 11.30 a.m. to St. Symion, and arrived at 7 p.m. Bivouaced in field close to wood.

8 September:

Left at 7 a.m. Guards Brigade formed advance guard, and were engaged with Germans, driving them back as we advanced. Saw dead Yager (sic) officer lying in field, and other dead Germans and carts lying about. Guards captured several machine guns which we passed on the road. We took up a salient position at La Pierre behind river. We arrived there and bivouacked about 9 p.m.[4]

9 September:

Marched at 4 a.m.; crossed river at Charly. All houses along river bank loopholed. Houses looted along the road, and empty bottles everywhere. The tables outside the houses were full of empty wine bottles and glasses. Germans did not hold the bridge over the river, although the house commanding the bridge was all loopholed for defence. Rumours of German ambush after we had passed through Charly. We halted for a long time on road. Received our rations and also filled water bottles from a nice spring near road. “A” and “C” Companies took up a line of outposts, the Gloucestershire Regiment on our right, and our Cavalry Brigade in front.[5]

10 September:

Marched off early and rejoined the main column on the line of march with “C” Company. After we had been marching for some time, information was received that the Germans were in front of a place called Haute Vesnes (sic).

The 6th Brigade deployed for attack. “A” and “C” Companies in reserve. The artillery came into action and supported the infantry, the German infantry being practically surrounded. They surrendered and were made prisoners after having put up a good fight. About 250 prisoners were captured. Captain Duckworth and Lieutenant Birch were both wounded.

“A” and “C” Companies were detailed to bury the German dead and collect rifles and bayonets of German prisoners left on the battle field. Nearly all the German dead had been killed by shell fire. We bivouacked in a field about two miles from the scene of the battle at Chevillon.

11 September:

We marched at 5 a.m. It rained hard nearly all day and we got soaked. Arrived at Cugny and went into billets in a large field at Wallee. The men were packed in very close into lofts, barns, etc., but anything was better than being out in the deluge. The officers lived with the farmer, and we got some butter, which was the first we had tasted for days. Slept on a mattress on the floor.

12 September:

Left Wallee at 5 a.m.; marched via Braine. The was evidence of an advanced guard action (cavalry). Passed many German dead and prisoners.

Halted at foot of hill. Climbed steep hill in torrents of rain. Went into billets at Monthuissart Farm. The whole of the 6th Brigade was billeted in the farm, and we were all very crowded. The officers shared a barn with the 60th Rifles. Post from England arrived soon after we billeted.

13 September:

Marched at 4 a.m., and after about three miles halted for most of the day. Heavy artillery battle going on in front. Headquarters 1st Army Corps close to us. Many aeroplanes coming and going with information. In the evening we advanced. Our heavy guns were in action on the left of the road, and firing at the enemy at a range of about 8,000 yards. Battalion went into billets at Viel D’Arcy. “A” Company went out on outposts. Found a strange cave with a man, wife, and children living in it on a hill.

14 September:

Lost my horse in the night, but found the veterinary officer had caught it. 5th Brigade across river Soupir, Moussy, Bourg line. We advanced via Pont D’Arcy to Moussy. Fighting going on all day by Guards Brigade on our left, and King’s Regiment on our right.

Part of the Battalion, including “A” Company, moved up to support the King’s behind Moussy. We were withdrawn and sent on outpost duty on canal, but relieved by King’s Regiment and returned to Moussy. “A” and “D” Companies on road outside Moussy in support, the remainder of the Battalion in billets in Moussy. Dug ourselves in on the road. It was a wet night.

15 September:

Still on the road. Shelled all day by ‘Black Maria.’ Lost a lot of men; some fearful wounds. Did what I could to tie up the wounds, and got covered in blood. Eventually I found I could not cope with the wounded, so sent a man to Moussy for a medical officer, but as he did not come, went in myself to bring him. Found him and he came back with me.

Soon after the arrival of the Medical Officer (Lieutenant Ball), Second-Lieutenant Miller and several men were killed and wounded by another shell, which burst in the road close to them. I assisted him to tie up the wounded. During the afternoon Lieutenant Rutherford was seriously wounded by a shell in the back. The battery of artillery near to us had thirty horses killed and a number of men killed and wounded. Dead men and horses were strewn about the place.

Private Littlewood, of the Company, showed great pluck in going for the stretchers on two occasions along the road to Moussy under a hail of shells and bringing them back with him and removing the wounded. It rained hard in the night, and we remained where we were for the night.[6]

16 September:

Still on the road, and were shelled. Tried to bury the dead. Dead horses smelt very bad, but it was quite impossible to bury them on account of the shells. A shell burst just above the Companies, and a lot of dug-outs fell in and buried the occupants. We had some difficulty getting them out.

In the evening the Battalion was sent across to reinforce the 4th Guards Brigade at Soupir. The German guns shelled the Battalion on the road between Mousssy and Soupir. The Company had several casualties on the way. A haystack on the road was set on fire by the German shells, and one of the men of the Company who was dead near the haystack was burnt to nothing.

“A” Company on the 15th and 16th of September had lost one man (officer) and 24 men killed and wounded. “D” Company had also suffered a number of casualties, including one officer. We returned to Moussy on the night of (the) 16th, and went into billets. The officers of “A” Company billeted with the Cure, who was a very nice man.

17 September:

In billets at Moussy. English mail came. Germans shelled the place during the day.

18 September:

We marched over to Soupir at 3 a.m. Remained on the road in Soupir all day and night. Came on to rain hard in the night. Dent and I got washed out of our bivouac and eventually took refuge in a barn. We were both wet through. We remained in the barn until morning.

19 September:

Got Company and self into billets. It rained hard all day.

20 September:

Still in billets at Soupir. In the afternoon “A” and “B” Companies and the Machine Gun Section received orders to proceed to Chavonne to assist the Wiltshire Regiment, who had been driven from their trenches by the Germans. On arrival at Chavonne we could see a large body of German infantry in the wood above the Wiltshire Regiment, who were occupying a sunken road on the side of the hill.

Moved out with the Company to attack Germans. Covered by artillery fire, got Company into wood, and then moved out with some scouts to reconnoitre the best way to get up to the Wiltshires. Found a covered way, and advanced with two platoons to crest of hill and dug ourselves in. Called for a volunteer to go to Wiltshire Regiment and find out where they would like to be reinforced. Private Mutlow volunteered, and went across the open and returned with the required information: he ran considerable danger in doing so.

The two leading platoons of “A” Company advanced and moved up on the flank of the Wiltshires. We were opened fire on by the Germans and lost twenty killed and seven wounded. There were a lot of dead men of the Wiltshire Regiment lying about. A man in “A” Company was hit in the head and fell on me, covering me with his blood. Sent a message back to the Commanding Officer, telling him what I had done and asking for the other two platoons of “A” Company to be sent up to occupy the trenches which I had evacuated.

In covering our advance the artillery made splendid shooting, dropping their shells right into the middle of the German infantry, and scattering them in all directions. The German infantry retired, and the Wiltshire Regiment occupied their trenches. The German machine guns opened fire on the Company, but fired very high. We withdrew in the evening, and returned to Soupir.

21 September:

Went into trenches north of Soupir. German trenches about 200 yards in front. Intermittent firing going on all day and night. Second-Lieutenant Gyde wounded in the head in the evening.

Ordered to send out a small patrol to find out if Germans occupied their trenches at night. Lance-Corporal Watkins took out patrol. Germans fired on patrol, and patrol returned, but on returning one of the four men was found to be missing. Lance-Corporal Watkins went out to look for the missing man, and found Private Hemmings shot through the thigh near the German trench; he carried him in under fire.”

22 September:

Relieved in the trenches by the North Stafford Regiment, and marched to Bourg via Chavonne for a rest. The Company billeted in a large barn, the officers in a house close by.

Our hostess (Madame Loiselle) made us very comfortable, and cooked for us. She told us she had had the Germans billeted on her three times, the French twice and now the British. She was very cheerful in spite of all. We slept in one room, two of us on the floor and two in the bed.

23 September:

Still in billets at Bourg. The General Officer Commanding the 2nd Division came round and saw the Battalion in billets, and was very attentive to the comfort of both officers and men. He spoke a kind word here and a kind word there, and much ingratiated himself with all he came in contact with.”

24 September:

In billets. Went round to the Battalion Headquarters, and saw Rev. E. R. Day (late Chaplain to the Forces at Lichfield), who had called in on his way through to the see the Battalion.

25 September:

Left Bourg at 2 p.m. (25 September), and marched to Soupir via Chavonne. “A” and “D” Companies went into the trenches in support of the Rifle Brigade (17th Infantry Brigade). A good deal of sniping going on. We dug ourselves in during the night; it was very cold.

26 September:

Shelled in the early morning by the German artillery. Received orders to return to Soupir. German snipers very active. Private Edge, of the Company, was shot through the head as he was leaving the trench.

Medical Officer (Lieutenant Ball R.A.M.C.) killed by a shell. The death of the Medical Officer cast a gloom over the Regiment. He had on many occasions shown great bravery in attending the wounded under heavy fire and he met his death attending a wounded man.

We went to billets at Soupir.

A brief report on the death of 7168 Private Thomas Edge appeared in The Birmingham Daily Post on 20 October 1914:

“Information has been received that Private F.(sic) Edge, a reservist in the South Staffordshire Regiment, was killed during the battle of the Aisne. Edge was married and leaves a widow and one child.”

Private Edge’s widow, Sarah, lived at the Bowling Green in Netherton. He had attested for the South Staffords at Brierley Hill on 22 August 1904, and was employed as a rivet maker at the time of his enlistment. His battlefield grave was lost in later fighting and Thomas is therefore commemorated on the La Ferte-sous-Jouarre Memorial. The register records that Sarah Edge had died at the time the information was compiled, and that Thomas’s parents, Edward and Mary Anne Edge, lived at 57a Waggon Street in Old Hill. Private Edge was aged 27 when he was killed.

Lieutenant William Ormsby Wyndham Ball B.A. (Dublin), M.B., Royal Army Medical Corps, is also commemorated on the same memorial. He was aged 24 when he was killed and was the son of Henry Wyndham Ball and Elizabeth Ball. William had played hockey representing Ireland six times during 1910 and 1911.

Captain Savage:

27 September:

Left Soupir at 4 a.m. (27 September) and went up into a wood behind the trenches, in support, and there dug ourselves in. In the morning heard a German band behind their trenches. At the end of the service the band played “God save the King” (the Prussian National Anthem). Very heavy rifle and artillery fire took place on our right during the night.

28 September:

Still in the wood. Thomas and I found a cave, and decided to explore it and see if there were any snipers in it. We took six men and explored it, but found no snipers, but used the cave for eating our meals in after dark, as we could cook in it.

29 September:

In the woods. A good many of the enemy’s aeroplanes about, and the men were told to get into their dug-outs as soon as a whistle was blown. The men had made themselves very comfortable in a short time they had been in the wood, there being plenty of brushwood and other materials about.

30 September:

In the wood. Men went down to a stream and had a good wash, but were shelled by Germans while washing.

1 October:

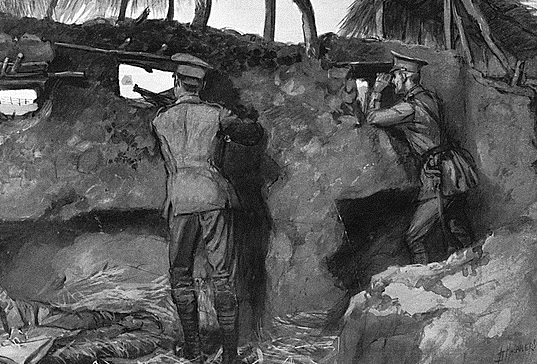

Went up in the trenches and relieved the Rifle Brigade in the trenches. Officers of the Rifle Brigade were very kind, and gave us some dinner. There was a very comfortable dug-out for the officers, including and underground kitchen and a place for servants. We also had a table. We lived very well in the trenches, and one day had a goose sent up from Soupir, where it was cooked in the bakery. The weather was fine, but the nights very cold, with white frosts.

2 October:

In the trenches. The Germans were rather troublesome, and kept sniping at us all day. Most of their bullets seemed to strike about six feet over the place where the officers took their meals, into a bank, and after a time quite a large hole was made in the bank.

3 October:

“Sent out four pairs of snipers (each pair provided with field glasses) on the high ground behind the trenches, where they had a good view, and were well concealed among the trees and long grass. Each pair took a section of the German trench in front, and after they had been firing at the enemy’s trenches for some time, the Germans ceased to snipe (at) us any longer. In the evening the Germans dropped some shells very near to us while we were at tea, and we took to our dug-outs very quickly, fortunately, nobody was hit.

4 October:

We were relieved in the evening in the trenches by the King’s Royal Rifles, and moved back to our old trenches in the wood in support.

5 October:

Still in support in the wood. A man in the Company slightly wounded in the chest by a spent bullet, which had to be pulled out.

6 October:

In the evening received orders to return to Moussy, via Soupir. On arrival at Moussy “A” and “D” Companies received orders to move up and relieve the King’s Regiment in the trenches. Saw Colonel Bannatyne,[7] of the King’s Regiment, for the last time; he was killed a few days later. Took over trenches at Beaulne Spur from the King’s in the dark, and the King’s withdrew.

7 October:

In the trenches at Beaulne Spur. Sent out reconnoitring patrol of ten men under Lieutenant D —- (Dent) to locate exact position of enemy. He approached within five yards of German sentry without being seen, and then withdrew and brought back plan of enemy’s position.

A number of our dead, belonging to Worcester Regiment, lying about near our trenches. We could also see a number of German dead on the opposite hill. Our dead had not been buried owing to persons moving about near the trenches having drawn a very heavy fire from the enemy. During the night Lance-Corporal Turner and a party of our men buried 17 of our own dead near the trenches, and their identity discs were sent to their Regiment. Company dug communicating trench to “D” Company during the night.

8 October:

Received orders to send out an officer’s patrol and endeavour to find out if the enemy’s infantry in front had been replaced by cavalry, and if not, the number of the regiment in front. Lieutenant D —- (Dent), with two sections, went out before dawn. After the patrol had been out for some time we heard a shot and screams. About ten minutes after two the patrol came in and reported that they had attacked the Germans, who had retired. The patrol came in soon after with a German helmet of the 13th Reserve Regiment. The officer and one of the men had crept up close to a German sentry, and the sentry, observing them, was about to give the alarm, when he was shot by the man with the officer (Private Simmonds).[8] The patrol then charged the Germans, who retired, and they returned with the helmet from the German who had been shot.

This smart piece of patrol work was carried out by the patrol without the loss of a man. The helmet was sent into Brigade Headquarters with a report. Captain Wilson, of the 3rd Battalion, joined the Company from home.

9 October:

Company returned to Moussy, being relieved by “C” Company in the trenches. We went into billets in Moussy at about 1 a.m. We went out with C.O. and D. (Dent) to reconnoitre better way to trenches through the wood in case companies in the trenches required reinforcements. We cut a way through the wood.

10 October:

Went out from Moussy with fatigue party and improved path cut through the wood on the previous day to the trenches. Moved up with Company to relieve “C” Company in the trenches. A heavy attack took place on the Queen’s on our left during the night, and we all stood to arms until it was over.

11 October:

In the trenches. Lieutenant S—— (Scott) took out a patrol at 5 a.m. to try and discover where the enemy placed their sentries at night. The same patrol went out in the evening to wait and watch the enemy put out their sentries for the night. Was fired at three times by a German sniper, who nearly hit me.

12 October:

Fairly quiet all day. The Berks Regiment carried out an attack on our left in the evening and set on fire some haystacks near the Germans. Some very heavy fire took place. Relieved in the trenches by “C” Company, and retired to our billets in Moussy.

13 October:

Moussy, in billets.

14 October:

In billets. The French came up and relieved the 6th Brigade except ourselves in the night. The 267th Regiment of the line was on our left. An officer came in and saw the Colonel in the afternoon. We went up and relieved “C” Company in the trenches in the evening. Firing started just as we got up, very wet. The men fell about a lot in the slippery ground.

15 October:

In the trenches. Gunner officers came round in the morning to look for German guns. We were relieved at 11.45 p.m. by a French infantry regiment in the trenches, and returned to Moussy.

16 October:

Marched from Moussy at 4 a.m., and arrived at Fismes in the morning, and went into billets there. Entrained at Fismes in the evening. The heavy artillery left before us.

17 October:

In the train. Arrived at Boulogne about 4.30 p.m. Saw some of the Naval Brigade, with armoured trains, in Boulogne, also a large number of Belgian refugees, a large number of whom were able-bodied men, and should have been fighting for their country. There had been a railway smash at the station the night before. We passed a large number of trains full of Belgian refugees. Arrived at Calais at 6.30 p.m. Arrived at Hazebrouck about 12 midnight.

18 October:

We went to Strazelle by train (five miles), and detrained there and marched back to Hazebrouck, which we reached about 4 a.m. The Company was billeted in a school, and we in a house not far off; we had some coffee and brandy on arrival in billet, and got to bed at 5 a.m. Had very good meals while in billet. Had tea at a hotel called “Fleu de Lap” in the afternoon. Post came.

19 October:

Went to a conference at Battalion Headquarters at 8.30 a.m. Left for Godewearsvelde at 4 p.m., and put up in a cafe there. Company billeted in a barn close to cafe.

20 October:

Left at 6 a.m. for Ypres. Road very bad. We could hear guns firing and also rifle fire on the march. We billeted in a school and were very comfortable; some of the Company in school, and some in a house close to it.

21 October:

We moved at 6 a.m., and remained on the road for some time. The 80th French Regiment passed us in the street, and were very interested when they were told we were the Staffordshire Regiment.[9] We were in reserve all day at Wieltje. The French 79th Regiment were near us in trenches. In the evening we went into billets at Potitie (sic – Potijze). Billets were very hard to find. Had to put Company in billets with French soldiers and Belgian refugees. Firing going on most of the night.

22 October:

Received orders to go out on my horse and reconnoitre the road to Zonnebeke in case Battalion was required to go out and reinforce Brigade entrenched near there. Met Major ——-, of the King’s, and we did the job together. Met Lieutenant F —— (Foster),[10] of the 1st Battalion, and several others of the Regiment whom I knew. Returned to Potitie (sic) about 9 a.m. Remained in billets for the rest of the day.

23 October:

Left Potitie (sic) at 1.30 a.m. for Pilkem (sic – Pilckem) to reinforce Brigade there. Arrived at Pilkem (sic) and moved out in the direction of Bixscoote (sic – Bixschoote) as soon as it was light. Heavy firing going on all round. We remained in the road in support for some time. The Loyal North Lancashires moved out to attack the German trenches, and the Battalion moved out in support. “A” Company on the right, “D” Company on the left.

We advanced under a heavy rifle fire, but there were several large farms which assisted us very much in our advance, screening us from view and rifle fire. Eventually, located the German trenches and by cutting holes through hedges we were able to get up to within about 200 yards of the enemy’s trenches. Lieutenant D—- (Dent) brought up his platoon in support, although badly wounded in the knee, but he could go no further. Heard later that Lieutenant H——— (Halewood) had been shot through the chest, and Lieutenant S—— (Scott)[11] killed. He had been sent with the Commanding Officer of the Loyal North Lancashires to bring us word regarding the place we were to reinforce them.

A platoon from another company tried to come up to my support on the left. A machine gun got on them, and I saw a number of men bowled over, only one officer and one man reaching the cover of the hedge. Sent a platoon under Captain W——- to hold a farm near.

Our field howitzers made excellent shooting, the shells dropping right into the German trenches, and after each shell a number of the enemy would run out of their trenches to the rear, but they were all shot down by us before they got far.

Gave orders to men to dig themselves in as enemy’s guns now turned on us. A large shell burst in front of us, and a piece entered and broke my arm; fortunately, it hit nobody else.”

Captain Savage was awarded the Distinguished Service Order, the announcement being published in The London Gazette on 18 February 1915, and again on 24 March 1915. He was also Mentioned in Despatches on four occasions during the war. Savage later held staff posts and was appointed a Companion of the Order of the British Empire in the King’s Birthday Honours on 3 June 1919 while a Major and Brevet Lieutenant-Colonel (Temporary Lieutenant-Colonel). He was the Commanding Officer of the 2nd Battalion for four years from 1921 and was placed on half-pay on 2 January 1925 before finally retiring on 2 July. Savage served as a councillor on London County Council between 1928 and 1931, when he represented Battersea North as a member of the Municipal Reform Party.

Lieutenant-Colonel Morris Boscawen Savage D.S.O., C.B.E. died at Lichfield on 11 June 1958.

Footnotes:

[1] Casualty” (Lieutenant A. A. E. Gyde), Contemptible: A Personal Recollection of the ‘Retreat from Mons’ by a British Infantry Officer (London: Heinemann, 1916), p. 12.

[2] Cox’s memoirs are held in the archives of The Staffordshire Regiment Museum. Later promoted Company Sergeant-Major, he was awarded the Military Cross, the citation for the award being published in The London Gazette on 13 February 1917:

“For conspicuous gallantry in action. Although wounded he continued to lead his men with great courage and determination. Later, he rendered most valuable assistance in organising the defence of the position.”

[3] On 5 September 1914, the Retreat from Mons officially ended and the first stage of the Battle of the Marne commenced as the French Armies began their counter-attack to push the Germans back from threatening Paris. The 2nd Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment reached Chaumes on 5 September. The War Diary records that since 21 August, the 2nd South Staffords had marched 236 miles.

[4] On 8 September, the 2nd South Staffords marched from their bivouacs south of St Simeon, via Rebais, La Tretoire and Boitron, before halting at La Noue for the night.

[5] The 2nd South Staffords had crossed the Marne at Charly, before advancing to Corpru during the day.

[6] Two officers had been wounded during the day, as well as several other ranks, while eight Privates and one Drummer had been killed.

[7] Lieutenant-Colonel William Stirling Bannatyne, the Commanding Officer of the 1st Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool Regiment), was mortally wounded at near Polygon Wood, when the King’s made an attack on the village of Molenaarelsthoek on 24 October 1914. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial.

[8] 6871 Private William Albert Simmonds was later awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for his actions during the patrol. The citation was published in The London Gazette on 17 December 1914:

“For conspicuous gallantry on 7th October (sic) in locating the enemy’s trenches by daring scouting at night, and subsequently rushing it with two sections, driving the enemy away.”

Simmonds had been drafted to France with the First Reinforcement on 27 August and was subsequently appointed Quartermaster, attaining the rank of Captain.

[9] The 2nd Battalion had been the 80th Foot prior to 1881.

[10] Lieutenant William Augustus Portman Foster. Promoted to Captain, Foster died of wounds on 11 November 1914 as a prisoner-of-war and is buried at Niederzwehren Cemetery: Plot III, Row G, Grave 7.

[11] Second-Lieutenant Basil John Harrison Scott. Aged 20 when he was killed, Scott was posthumously Mentioned in Despatches and is commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial.